With the likes of Sam Altman and Elon Musk dashing about, we crouch for shelter now in an era where well-funded high-tech bros can live a life that was once reserved only for Doctor Strange.

With the likes of Sam Altman and Elon Musk dashing about, we crouch for shelter now in an era where well-funded high-tech bros can live a life that was once reserved only for Doctor Strange.

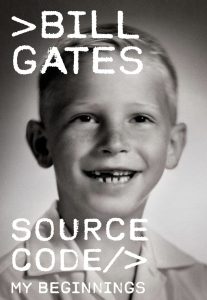

That tends to make Bill Gates’ “Source Code: My Beginnings” (Knopf, 2025) a much more warmfy and life-affirming book than it might otherwise have been. In this recounting of his early days, and founding of Microsoft, he paints a colorful picture of a bright and excitable boy making good. Much of Source Code is set in “the green pastures of Harvard University.”

The boy wonder to be was born in Seattle in 1955, when computers were room sized, and totally unlike the consumer devices which humans now ponder like prayer books as they walk city streets.

His family was comfortable and gave him a lot of room to engage a very curious imagination. His mother called it precociousness, and it’s a trait he dampered down when he could. He had a fascination with basic analytical principles, which held him in stead when the age of personal computers dawned.

Like others, his interests had been piqued by the Cold War Space Race. Those interests were dramatically boosted by the Seattle World’s Fair in 1962, centered around the Space Needle. He was 7 – and he was there.

Gates has an easy way with telling the story – for me “Source Code” is a good read. After the initial pages establish him as both nerdy and normal – he programs a DEC minicomputer by night, but owns a Jimi Hendrix record – as a boy scout hiking he’d do programming problems in his head. Telling in this tale: The struggle of the young Gates to gain access to any computer he could get his hands on.

But it’s in the leaving Seattle for Cambridge and Harvard University where fate begins to beckon, and the narrative starts really rolling.

He comes East as an inveterate young hacker in a world where the computer was still very new. New and non-ubiquitous. But he scouts around the Harvard campus, where he is soon tapping into large machines at night, much as he had in high school. For a Boston boy like me, there are parts of Source Code that ring especially, because the story follows breadcrumb cites in Boston and Cambridge haunts. In Gates telling, these places seem naturally infused with the glow of personal memory and human journey.

In Boston-adjacent Cambridge, well within the circle of Route 128, he finds himself in what was then an important computing nexus, far surpassing Silicon Valley that would surpass it in time.

At the Font

Gates has a great sense of detail.

When he first enters the Aiken Computation Laboratory on Cambridge’s Oxford Street, Gates encounters an original computer era relic – Howard Aiken’s Mark 1.

While smoking a Parliament cigarette, the lab director interviews young Bill.

Gates recalls how classmates banded together in study klatches to surmount “Harvard Math 55” and its somewhat obscure teacher. He writes:

“…while the rest of the dorm was partying over garbage cans of ZaRex fruit punch and vodka, we puzzled through math problems, hung out and drew one another into debates or questions that tested our thinking skills or trivia knowledge…There was a certain purity to friendships back then that I appreciate more now than I did at the time.”

They’d break up late night study sessions with pinball playing or TV news watching at the Student Union. Or, a late-night dash for the last pizza of the day at Pinocchio’s pizza place in Harvard Square – still there, still one of the few vestiges of that lost time. I wonder if I could have been grabbing that late night pizza along with him in 1975.

Gates’ deep dive in math at Harvard convinced him he didn’t have the special insight that an academic math career might take – that he didn’t shine like a crazy math whiz diamond. He could visualize himself teaching at a university, not good enough to do groundbreaking work in math. And he wonder about his future.

At a loss for what to do he mused. One friend told him: “You’re really good at the computer stuff. Why don’t you do that?”

So, yes, go thee to the computer room, young man!

It was a natural fit. As young as he was, he was very aware that the computer world was nearing the edge of momentous change. He followed the birthing of personal computing in the arcane journals of the time. But he came to this ponder with a well-developed view of the minicomputer. At Harvard he found one or two of them, and signed in.

He holds a particularly fond location in memory for the Lab’s DEC PDP-1. He writes:

“If the PDP-10 at the time was the equivalent of a late-1960s muscle car — known for raw power — the PDP-1 was a ’57 Chevy — old, not so fast, but with lots of style.” The PDP-1 was known to support an advanced interactivity, compared to the mainframe, and it promoted a programming style that influenced Gates’ thinking.

That machine has a story. And Gates re-tells it here.

There are wires hanging from it where Ian Sutherland had connected the first head-mounted virtual reality device.

There was a joy-stick left by the work of Sutherland’s students — Ed Taft or Danny Cohen — who devised a flight simulator on this machine.

The PDP-1 was the locale where Taft and such as Bob Metcalf did networking and graphics work — that before going on to West Coast’s Xerox Parc, the microcomputer hotbed where they devised PostScript and PDFs, ALOHAnet and Ethernet, and more.

Out of Town, Man; Far out

In Gates memory trapped cozily in amber we see the magic of loose college days. Soon, he’d been joined in greater Boston by his older cohort in Seattle computer hacking, Paul Allen. They didn’t know what it would be called, but they were finding their way to founding Microsoft.

This creation story always turns to Out of Town News, the near-landmark newspaper and magazine kiosk in the center of Harvard Square. Historic — if just for the fact that Paul Allen was inhaling the tech magazines that could be found there. That meant new and back issues of Popular Electronics, Datamation and Radio Electronics. These were filled with spec sheets for computers and components. The big news of the day was the Intel 8080 microprocessor that Allen and Gates immediately saw as a next step in computer evolution.

Over Mai Tais (Allen) and Shirley Temples (Gates) at Aku-Aku, a Polynesian restaurant near Fresh Pond, they would sift through ideas for computer companies. Even then, Gates was prescient, as he was growing cool to the idea of building hardware, a domain that was much more capital intensive as compared to software. Allen and Gates had drawn such conclusions from first principles, having encountered obstacles in a fledgling cottage business for computer-based traffic management as lads back in Seattle.

They kept a close eye on the first small computers – hobbyist kits mostly, requiring soldering skills – that were being marketed around Intel’s 8008 and later 8080. The epiphany came when Allen slogged through sleet from Out of Town News, arriving at the dorm breathlessly.

He’d read an article about the MITS Altair Computer. Yes, Gates is good at remembering. They had visualized something like this, and were shocked that this revolutionary product could happen without them. As it turns out, it needed software.

Based on the 8080, the Altair would sell for less than $400, the cost of a color TV at the time. It has no keyboard. Instead, it sported toggle switches for input. The duo’s phone calls and letters to MITS disclosed that the makers hadn’t really thought too much about what software would bring the machine to life. Gates and Allen spent the better parts of three months writing a Basic Compiler Interpreter that fit the bill. The rest is a history to be continued as Gates fills out his life’s tale in upcoming segments.

Source Code is an important story. With Steve Jobs, Bill Gates uneasily shares the leading role in the Personal Computing era – and he gets a chance here to tell it his way.

No, not a seer, really. Or was he? His difficulty in getting computer access as a youth cued him to what the world would be like if computers were affordable, and in each household. Source Code tells how he started out on that expedition. – Jack Vaughan