With the likes of Sam Altman and Elon Musk dashing about, we crouch for shelter now in an era where well-funded high-tech bros can live a life that was once reserved only for Doctor Strange.

With the likes of Sam Altman and Elon Musk dashing about, we crouch for shelter now in an era where well-funded high-tech bros can live a life that was once reserved only for Doctor Strange.

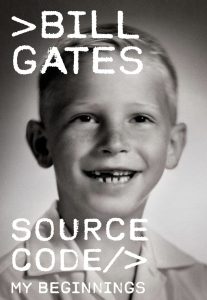

That tends to make Bill Gates’ “Source Code: My Beginnings” (Knopf, 2025) a much more warmfy and life-affirming book than it might otherwise have been. In this recounting of his early days, and founding of Microsoft, he paints a colorful picture of a bright and excitable boy making good. Much of Source Code is set in “the green pastures of Harvard University.”

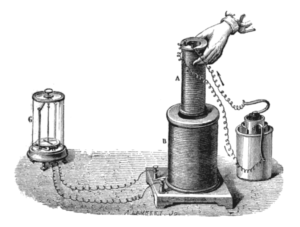

The boy wonder to be was born in Seattle in 1955, when computers were room sized, and totally unlike the consumer devices which humans now ponder like prayer books as they walk city streets.

His family was comfortable and gave him a lot of room to engage a very curious imagination. His mother called it precociousness, and it’s a trait he dampered down when he could. He had a fascination with basic analytical principles, which held him in stead when the age of personal computers dawned. [Read more…] about Source Code: Bill Gates’ Harvard Days